Enjoy this guest post by friend of Saddle Seeks Horse, Emily Esterson. Emily is someone I met through American Horse Publications and clicked with immediately (I could tell we were the same level of horse crazy). Emily is both a fox hunting and eventing enthusiast and recently had a remarkable opportunity to ride with Buck Davidson.

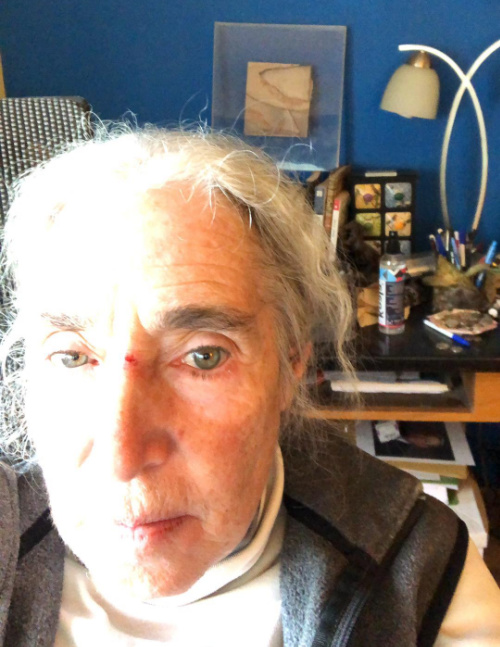

“It looks worse than it is,” said the text message I didn’t send to my husband, meant as a warning to not be alarmed by my freshly bruised, possibly broken nose.

The nose was the innocent victim of my bad jumping habit—burying my hands on my horse’s neck— as well as nerves, not drinking enough water, frozen toes, and an inability to remember and execute the 10,000 little technicalities necessary to jump the left side of the two-stride combination, sit up and ride to the big oxer.

Not quite lawn-dart-fall, more like a tumble. Lucy (bless her) just couldn’t get off the ground as I had buried my hands in her neck and landed on it after the first element. We crashed through #2 and if I had been sitting up, I would have been fine. Instead, the nose hit something… not sure what… and we landed in a heap of rails and bruised ego.

A bit of background: As New Mexico isn’t exactly a regular stop on top level clinicians’ calendars, I take advantage of the opportunities to gain wisdom when they arise. A few months back I rode with Laine Ashker (so positive, so fun) and this time I rode with Buck Davidson.

I’ve always been a fan of Buck’s—something about his riding style, his unlikely physique (he is not all legs, like William Fox Pitt), and his powerful athleticism I’ve found appealing. And although I’m not prone to being a fan-girl (thanks to decades as a journalist), when it comes to highly accomplished equestrians, I’m a little bit weak-kneed, and perhaps that got to me just a bit.

Buck is very good at teaching. He’s on the quiet side, preferring the conversational approach that happens one-on-one with riders after they’ve completed a round. He’s likely to trot over to where you have finished your round and dissect it with you. This may be more useful than the shouting-across-the-arena-approach because you’re able to ask questions and really listen, rather than straining to hear while also making that sharp right turn. But more importantly to me, the sign of the good clinician is one who can stop the action when things go awry and back track, patiently revisiting the problem, making the exercise more friendly, gradually building up the rider’s confidence again until they are successful.

I observed Buck do this several times during the two-day clinic and experienced it myself post oxer-crash. Day one involved circles. Lots of circles. Ten-meter—or even smaller–circles to gain balance, to engage the inside hind leg, to encourage push, and to teach riders to use the outside aids effectively in the turns. Cones guided our circles before each jump. The key was to keep riding forward while not drifting out.

We had practiced this same exercise at home recently, and Lucy is small and catty, so we were relatively successful although at times I felt like I was cornering too sharply on a motorcycle, one rpm away from falling sideways. In a later group, another rider had trouble with this, and her horse became a bit fractious. Buck patiently simplified the exercise, breaking it down to walk, then trot, working with the rider until both she and her horse had a better feel of how to get those circles tight and balanced. This was the theme of the day.

Day two saw a focus on jumping courses, but what stood out most was that success here wasn’t about the strides. Lots of us, me included, worry about “seeing the distance.” Buck didn’t want us to pay attention to that. Instead, it was about precise lines: Ride to the right stripe on that jump, ride to the left on this other one. Go left of that cone, right of this one. This was harder than it sounds. I’ve spent a lot of time practicing getting straight to the center of any jump. But now Buck instructed us to focus on one side or the other side, depending on which way we were turning after the jump. If we did that with enough power behind, the distance came easily, no counting necessary. Lesson learned? It’s about the line, not the distance. It’s about putting your horse exactly where you want over the jump. The more advanced groups got to put their circle skills to the test, riding tight turns to precise areas of the jumps.

I was, without doubt, the oldest person in the clinic, and after a wreck, it’s very easy for me to go to that dark place of near-post-middle age: What am I doing here? I am too old for this. What am I trying to accomplish? I’m not going to the Olympics. And why am I STILL leaning forward, and why is riding well just so damn hard? But lifelong learning is in my blood, and I have indeed learned from these clinicians: The lessons are the same, and any educator will tell you that repetition is the key to education: keep going forward, sit up tall, ride with outside aids, straight is paramount even if it is just for a stride or two before or after the jump. Keep riding through the cones.

Side note: Thanks to the Canterbury Eventing group of Heather Drager, Ashley Fischer, and Kelly Shear for being game and ambitious, juggling jobs and families and competitive riding in a literal eventing desert (bless them for their try) and for continuing to bring these clinicians to our dry little corner of the planet.

Emily Esterson is a writer, editor, professor and eventing enthusiast. She teaches Equine Journalism at University of Guelph in Canada. She is the author of The Ultimate Book of Bits. You can find Emily online at https://e-squarededit.com/